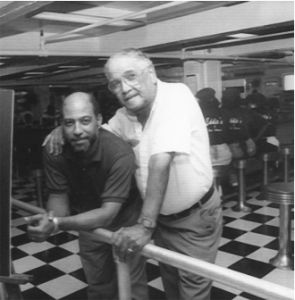

Wayne Baquet in front of a portrait of his father, Eddie at Li’l Dizzy’s Cafe

Share This

Print This

Email This

The Baquets: “Quite a History”

South Writ Large had the opportunity to sit down with Wayne Baquet, owner of Li’L Dizzy’s Cafe in New Orleans to learn more about the history of the Baquet family.

New Orleanians anticipate good food when they venture out for a meal at any one of the restaurants that are scattered throughout the city’s neighborhoods. Even Bourbon Street, known for its tourist trappings and neon-colored drinks, hosts Galatoire’s, a beloved establishment where you’d be hard-pressed to leave without an extra helping of crab meat on your entrée. New Orleans doesn’t just pride itself on the taste of its food, but also on the traditions that have given birth to the particular flavors, ones that are often passed down to family members, to be embellished upon by succeeding generations.

Wayne Baquet is the current restauranteur of one such family, boasting four generations of accumulated acumen since the 1940s. Twelve restaurants later, Wayne Baquet is still at the helm of his family’s business, serving up Creole cuisine daily at Li’l Dizzy’s Café on the corner of Esplanade and N. Robertson Street in the Tremé neighborhood. Li’l Dizzy’s is a Creole establishment in ownership, culture, and cuisine – one of the few remaining in the city. Li’l Dizzy’s serves what most discerning customers claim is the best gumbo in the city as well as other Creole food staples such as jambalaya, homemade hot sausage, and crawfish bisque. In 2009, Wayne assembled The Baquet Family Cookbook: Four Generations of Creole Cookin’ in New Orleans, with assorted family recipes that have evolved over time.

The Baquet’s foray into restaurants began in 1940 with Ada Baquet Gross and her husband, Paul Gross, who opened a twenty-four-hour restaurant on Bienville and Roman Streets. Wayne points out that Paul, “was a real character. He’s mentioned in many publications as being a pimp. I knew him as a kid as having all tailored-made three-piece suits. But Ada had the money. Ada opened up the restaurant and put his name on it, so it was called Paul Gross Chicken Coop.” Ada enlisted the help of Eddie Baquet, Sr., Wayne’s father, who was a mail carrier by day and the restaurant manager at night. Wayne recalls, “one of the real attractions of the restaurant was they had an oval window with a neon sign that said, ‘Air Conditioning.’”

In 1966, Eddie decided to hang his own shingle, so he bought Goodfella’s Bar on Law Street, renamed it Eddie’s, and moved his wife, mother and father, five boys (Eddie, Jr., Wayne, Rudy, Dean, and Terry), and a daughter-in-law into the back. Eddie served as the butcher and Wayne’s mother, his aunt Anna, and his grandmother were the expert cooks. Wayne declares, “Boy, they could cook! . . .We were in the middle of the 7th Ward and everybody said, ‘You can’t do business in the 7th Ward. That’s the mecca of Creole cooking.’ This is no joke: when we started cooking gumbo and crawfish bisque and things like that, fried chicken, them people came in droves.”

- Eddie Baquet

- Eddie and Myrtle Baquet

- Eddie and Myrtle Baquet

With Eddie’s well underway, Wayne took a job at as a manager at Woolco Department Store on Veterans Highway, where he gained business savvy. Upon the urging of his family, he returned to work full-time at the restaurant and immediately set out to update Eddie’s, making it more efficient and modern. “Back in the day, my parents didn’t know business. They didn’t understand it. My dad carried his money in his pocket instead of having it in a bank. Love him to death, but he was from the old school.” Wayne helped the kitchen transition from a made-from-scratch operation to a fully prepped kitchen. He also introduced a cash register and a ticketing system with numbers rather than recording orders on paper used to wrap sandwiches.

With Wayne’s success and ambitions, he opened a number of other restaurants across the city. In particular, Wayne and his wife, Janet, opened Café Baquet’s on Washington Avenue, which he ran for more than eight years. Wayne recalls one story that underscored their influence on local cuisine: “This sounds crazy, but the biggest Popeye’s they had in the city back then was on the corner from Café Baquet’s . . . What we did back then was make our own biscuits. And I would sell two hundred to three hundred biscuits every morning. So I would go there at like 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning, when Juanita was fixing coffee and prepping everything else. Then all of a sudden, I turn around and guess who took over the biscuit world? So that was the first [Popeye’s] to make biscuits. I said, ‘Look at this! Check it out!’”

At his parents’ prompting, he sold Café Baquet’s to return to Eddie’s in order to relieve them as they aged. “Pops told me, he said, ‘I’m ready. I’m ready for you to run this place.’ . . . He was happy. He would come in and give the children mints and hold the children while I did all the work.” As part of revitalizing Eddie’s, Wayne came up with an all-you-can-eat buffet for $4.95 on Thursday nights, which was wildly popular and kicked off a tremendous weekend’s worth of business each week. Eddie’s continued to be a hit, and Wayne was called upon to run the café at Southern University and the Krauss Department Store lunch counter, and he opened additional restaurants all over the city from Poydras Street in the Central Business District to Gentilly and New Orleans East. Eventually, at the encouragement of his son, Wayne, Jr., he purchased what would become Zachary’s, located in a beautiful Creole cottage on Oak Street, which was beloved during the eleven years it was open.

- Eddie, Sr., Eddie, Jr. and Wayne Baquet

- Eddie, Wayne, and Janet Baquet

The Baquet restaurants have long been important fixtures in New Orleans’s lively culinary scene, but the family is also known for other accomplishments, especially music and journalism. While Eddie, Jr., Wayne, and Rudy showed interest early on in taking on the daily grind of the restaurant business, their other siblings pursued careers in journalism. Dean is the executive editor of The New York Times and Terry is the Print Editor at The Times-Picayune.

In 2004, Galatoire’s hosted a big party thrown in honor of Wayne Baquet’s retirement from the restaurant business. During the party, Wayne remembers saying to himself, “Who are they kidding?! Really and truly.” It was not long before Wayne purchased Li’l Dizzy’s, which was open nearly a year before Hurricane Katrina hit in August of 2005. Wayne evacuated to Atlanta with his family, where he had the opportunity to open a restaurant that was partially bankrolled, but decided to come home to re-open Li’l Dizzy’s. According to Wayne, it was “the best move I made, getting Li’l Dizzy’s open fast and early because they had so many people coming back to check on their property [who] wanted to get the New Orleans food, wanted to get the New Orleans breakfast, red beans, and the hot sausage, and the gumbo. I mean, we had people around the block. We were one of the first restaurants open.”

The thing Wayne is most proud of over the arc of his career, he says, is “that I’ve employed hundreds of people who went on to do better things, many of them went on to do better things: college graduates, policemen that come in here who were my busboys.”

Fast forward to 2017 and Li’l Dizzy’s is still hopping, though the Treme neighborhood is changing along with all of New Orleans from a traditionally historic African American neighborhood to one that reflects the new diversity of the city. Wayne points out, “Li’l Dizzy’s I think is as well-known internationally now as [it is] nationally. I’m going to say that on busy Sundays, and Saturdays and Fridays, twenty percent of our people that come in here are from out of the country . . . We get people from all over. We also get a better cross-section of people because the neighborhood has changed.” Despite the changes that are occurring in the make-up of the neighborhood, Wayne is quick to note of his customers, “We don’t care how they come, as long as they come!”

FUN!

Dean may be the most famous Baquet today, but in New Orleans and especially, in its Creole community, Wayne is thought of as a sage — politically, socially, and religiously engaged.

Just love this, especially the sound recordings. What a glimpse into the history we know in our guts but are so glad to read with our eyes!

I’m old school and definitely remember Eddie’s on Law Street, as well as all their other restaurants…keep rolling brother!

This is a wonderful article. I agree that the sound recordings with the restaurant activity in the background add to the richness of the story. I have to get a cookbook.

Where can I buy the Baquet Family cookbook?

I want the cookbook!

Please help!

you can call or email for ordering cookbook here https://lildizzyscafe.net/new-orleans-treme-lil-dizzys-cafe-food-56458

As of November 2021, The Baquet Family Cookbook

$15.00/Unsigned$20.00/Autographed

.

The best food in New Orleans .La.my favorite place.