The Last Wolverine

This essay was originally published in Unarmed but Dangerous: A Withering Attack on All Things Phony, Foolish, and Fundamentally Wrong with America Today (1995).

Somewhere, reviewing Al Stump’s definitive biography of Ty Cobb, a disillusioned baseball fan must have written, “It’s like digging him up and driving a stake through his heart.”

It’s just like that. My only concern was that Stump’s stake isn’t sharp enough to do the job. With the possible exception of Adolf Hitler, Ty Cobb must be the most frightening human being I’ve ever encountered in a biography. And some comparisons favor the Fuhrer.

Hitler, by all accounts, was unfailingly kind to his dogs. Cobb loved to kick hunting dogs as much as he loved to spike third basemen.

Tommy Hitchcock, the great polo player, played a chukker or two with the great baseball player and was nauseated by the way Cobb would “whip the hide off his ponies.” But he treated animals better than he treated most people. This was a man with an incredible history of beating people. Not defeating them, mind you, but thrashing them. His victims included his wives, his children, his teammates, opponents, fans, umpires, policemen, and dozens of unfortunate waiters, cab drivers, bartenders, and desk clerks.

Cobb boasted that he beat a man to death in Detroit, a mugger who tried to flee when the ballplayer pulled his pistol. No one questioned his courage. He took on anyone, including prizefighters. But he seemed to specialize in women and black people. A violent racist, he beat up blacks just for touching his body.

Detroit teammates once pulled him off a black laundrywoman he was trying to strangle. She was luckier than his son, Ty Cobb, Jr. When the boy flunked out of Princeton, his father showed up at his rooming house with a bullwhip and beat him raw and bloody.

If I’d had a father like Ty, Jr.’s, I might have been a Rhodes Scholar. Cobb was a human wolverine. Armed and dangerous, a law unto himself, he was unquestionably insane.

If he had been less gifted at playing baseball and making money—he was a genius at both—he might have spent most of his life in prisons and asylums. Instead he was an intimate of presidents, tycoons, and movie stars, and the idol of generations of innocent American boys. One who grew up on his exploits was Joe DiMaggio; years after both of them had retired, Cobb limped into Toots Shor’s saloon, and DiMaggio whispered “Here comes God.”

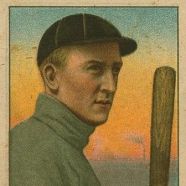

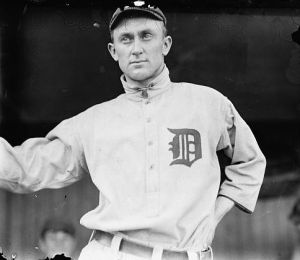

I was another believer. I was a strange ten-year-old, better at memorizing statistics than hitting fastballs, and I used to recite Cobb’s astonishing statistics to anyone who would listen. I even liked to say his name, “Tyrus Raymond Cobb,” for its virile rhythms. I tore that famous picture out of the Sporting News, the one where he’s sliding with his face in full profile, like an eagle in a baseball cap, and taped it over my bed.

I made a shrine for a psycho. Someone should have told me. Did my Dad, a baseball addict of Dimaggio’s generation, understand that Ty Cobb was a sociopath?

Boys have to grow up. But it’s rotten luck to learn this whole story forty years later, when I’m down to my last few illusions about baseball.

How do you defend a society where Ty Cobb could pass for a hero, or even pass for normal? There are grave doubts that he was even honest. Accused of throwing a game for gamblers, Cobb—who played poker at the White House with Warren G. Harding—enlisted the support of several U.S. senators and bullied and lawyered the commissioner of baseball into submission.

If you’re a tennis purist who thought John McEnroe was a national embarrassment, consider Ty Cobb. He survived and prospered, with his image relatively untarnished, through six decades of psychotic belligerence and criminal assault.

Cobb found the crack in the American psyche where athletic competition confuses itself with warfare, and he pushed until it was just wide enough to let him through. It’s no coincidence that Gen. Douglas MacArthur was his biggest fan.

His sickness was a distorted reflection of our own. You can make a case that he influenced the outcome of more major league baseball games than any player who ever lived. The question is whether that achievement means anything at all, considering the pathology of the athlete and the human cost he incurred.

At ten, I would have waffled on that one. Now it’s clear to me that the answer is “No.”

I never went along with the conscientious objectors of the playground, who preach that competition itself is a disease. For individuals of ordinary temperament, athletic competition is a healthy outlet for aggression. Muscular Christians tell us that courage, character, discipline, and self-esteem can be found on a playing field, and in ordinary cases I think they’re right.

The problem isn’t that competition is a disease, but that it attracts and rewards the diseased. Winning at any price is a principle that puts a premium on the marginally deranged. Their worst behavior is not only excused but rewarded, and reinforced.

Ty Cobb was the extreme. It appears that he went completely around the bend at eighteen, when his mother killed his father in a shooting that was never fully explained. But he shared some classic symptoms with other famous psychos of sports. He collected every book ever written about his idol, Napoleon Bonaparte. “He knew how to win against the odds,” Cobb told Al Stump.

When his minor-league roommate beat him to the bathtub after a ballgame, Cobb, seventeen years old, pitched a fit and snarled, “I’ve got to be first at everything–all the time.”

That wouldn’t sound psychotic to Pete Rose, the most aggressive ballplayer of his time and the man who finally broke Cobb’s fifty-year-old record for career base hits. If Cobb was a sociopath, Rose was only a belligerent creep. Rickey Henderson, who owns the stolen-base record Cobb held for half a century, was merely an obnoxious jerk. Leo Durocher, no sweetheart himself, was probably speaking for most ballplayers when he said, “Nice guys finish last.”

I could fill pages with the names of successful athletes who are certified creeps, bullies, woman-beaters, megalomaniacs, and unpunished criminals. But Ty Cobb’s most direct descendants, the true heirs to his mantle of meanness and menace, are some of our so-called “college coaches”—these glorified gym teachers who cover their trophy rooms with pictures of Gen. Patton.

Among the weirdest, most pathetic cases were the late Woody Hayes, who ended his career by punching a kid on the other team, and Jackie Sherrill, who motivated football players by castrating a bull on the practice field. But watch the faces on TV, through just one season of football and basketball, and you know half these coaches would sacrifice their first-born child for six more seconds on the clock.

Pathology is rampant. I even heard people defend Bobby Knight of Indiana, a festering head case who kicked his own son on national TV. Swollen with self-importance and sneaker payoffs, insulated from reality, crazy coaches threaten boycotts and concoct wild nonsense about minority opportunity when the NCAA tries to limit their scholarships. Grown men like Temple coach John Chaney, arrested in adolescent hostility, threaten to kill each other when twenty-year-old athletes disappoint them.

I remember writing, years ago, that coaches are people who come unglued under the pressure of pretending that something obviously trivial—winning games—is a matter of life and death. But these celebrated outpatients live in a world we made and maintain for them, a world where no one ever questions the importance of winning these games.

If Bobby Knight thought he was the only person in the world who gave a damn whether he won more college basketball games than Dean Smith or Adolph Rupp, would he have lightened up and treated players and sportswriters like human beings? That’s a long shot, I’m afraid. Coaches with perspective are eliminated at the high school level. If you’d rather be loved than feared, if you’d rather be a loser with friends than a winner with sycophants, if you walk away from the gym with a smile win or lose, I’ll bet my pension you never coach in Division I.

If Knight and those other winners are ever lucid enough to wonder how things turn out for guys who will kill to win, they’ll read Cobb : A Biography by Al Stump. Or at least see the movie, starring Tommy Lee Jones as Ty Cobb.

They called Cobb the “Georgia Peach.” He was so famous that when some wag hung the same nickname on Joseph Stalin, everybody in the United States got the joke. In Cobb’s papers Stump found fan letters from Mark Twain, Thomas Edison, Theodore Roosevelt, William Randolph Hearst, and Ernest Hemingway.

But after he retired he was unable, with millions of dollars from Coca-Cola investments, to buy his way back into the game. He played twenty-four years in the American League and left without a single friend. Eventually he alienated everyone, including his children and his family. He terrified nurses and servants, so he lived his last years alone and sick in a big house south of San Francisco. He died at seventy-four of cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and alcohol. Except for a couple of old teammates who forgave him, baseball ignored his funeral.

I have a rather unpleasant “brush with fame” story to tell about Cobb. In 1939 my mother was admitted to Stanford. My grandparents sold their San Francisco home to move down to Atherton to be closer to their daughter. They brought with them a boston terrier named Tuck. In those days Atherton had just undergone a division of large estates, and fences at that time were scant. Ty Cobb lived on a cul-de-sac behind my grandparents property, and it was on that street that the dog wandered one night. The police brought the dog to my grandparents, dead from a bullet wound. While no one could not be absolutely sure it was Cobb, the body had been found outside his residence.

John Richards:

There is a lot of indirect implications here. Just because you believed that Mr. Cobb killed your dog does not make him guilty. Mr. Cobb loved dogs and would never kill an innocent dog or animal. Please do not spread this type of propaganda about Mr. Cobb unless you can bring forth direct or material evidence to support your claim.

Did other people live around your home? Did you see Mr. Cobb shoot your dog? Do you have proof that Mr. Cobb possessed the same bullets or fragments that you found in your dog? Has your parents ever had an argument? Could your Dad have had access to your dog? Could it be more likely that your Dad shot your dog to get back at your mother? Do you understand that these questions contain a more sense of probability than the story that you told. Maybe, just maybe, Mr. Cobb did not kill your dog!

Opposition isn’t the same thing as discussion, and responding usually works better than reacting. And it’s always good to do one’s homework before entering into any debates where facts are needed.

I’m sure that with people like Cobb, killing a dog is no big deal. Like killing a mouse or a rat. Luckily he never shot your mother!!

Al Stump was an admitted liar who created many of the myths he included in his book out of whole cloth. If you are interested in a factual account of Cobb’s like purchase a copy of Leerhsen’s book, “Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty.” Well researched with sources included. You will learn that Cobb was not what you’ve been told or read about. Stump’s piece was a terrible injustice to Cobb’s legacy.

“Where there’s smoke, there’s fire”? If Cobb did half the stuff his worst critics said he did, I’d say the man was pretty awful. Both of these things could be true: Cobb was one of the greatest players who ever set foot on a baseball diamond – and – he was a terrible person.