Whole Hog, Partial Acceptance: The Problematic Commensality of Fourth of July Barbecues in the Antebellum South

Now that the temperature is rising in the Northeast and I begin the annual tradition of rolling my Weber grill back onto our patio, I am reminded of the complex and problematic history of barbecues in the United States. I can’t help it: such “bubble-bursting” thoughts are a frequent side effect of studying history. In the following excerpt from my upcoming dissertation, “‘I Choose to Sit at the Great National Table’: American Cuisine and Identity in the Early Republic,” I detail some of the social and racial inequities inherent in barbecue feasts, particularly Fourth of July celebrations that praised the benefits of American independence while simultaneously ignoring certain oppressed and enslaved populations. My intent with this passage is not to ruin anyone’s Fourth of July weekend, but I do hope to give you pause to reflect on the underlying cultural implications of celebrating our seemingly benign holidays and traditions. Enjoy your hot dog!

Fourth of July barbecues were important cultural celebrations in the early American Republic that highlighted the young nation’s attempts to form a communal identity. The obvious correlation between patriotic acts and the celebration of national independence aside, Fourth of July celebrations also instilled the concept of a shared American identity through the incorporation of large, festive, and lavish feasts to commemorate the occasion. Primarily in the southern and western states, a community barbecue became the symbol of the supposed abundance and convivial nature of American society. Yet these celebrations also ironically exposed deep-seated cultural hierarchies that ultimately revealed a nation divided and at odds with its own celebrations of unity and independence.

The American minister Charles A. Goodrich detailed the cultural significance of barbecue and its impact on American nationalism in his 1836 travelogue, The Universal Traveller. “Among the amusements of the people of the Southern States,” he wrote, “we find the Barbecue, and it is generally [considered] … an act of hospitality.” Goodrich described how gentlemen from throughout the region would chose to “unite for the purpose” of roasting “some savoury animal whole … after the manner of the ancients.”[1] The spirit of unity and community inclusiveness was evident in Goodrich’s review of the event, but more importantly, so too was the connotation and connection of the barbecue to American Indian society. His passing reference to the “manner of the ancients” alluded to the origins of the practice of barbecuing: a practice first observed and recorded by European authors in America as early as the sixteenth century.[2]

Open-flame roasting was of course a cooking technique almost universally practiced, but the specific spit-roasted, whole-animal methods of native peoples were of great interest to early European colonizers. By the mid-nineteenth century, the practice had become deeply ensconced in American national society even as the word “barbecue” itself remained associated with native populations and cultures.[3] A slow process of dissociation from American Indian cultures and appropriation into European society began early, however, and ultimately helped to distance barbecues from their supposed native origins. Goodrich’s passing reference exemplifies a cultural and intellectual evolution of the cooking practice away from its indigenous provenance and toward a supposedly unique American style.

American author and traveler Charles Lanman reiterated this evolutionary dissociation in 1850 when he (incorrectly) asserted that the word “barbecue” was in fact not American Indian in origin, but rather “derived from a combination of two French words signifying “from the head to the tail, or rather according to the moderns, the whole figure, or the whole hog.” Lanman conceded that, “By some, this species of entertainment is thought to have originated in the West India Islands.” Without any proof, he concluded it to be “quite certain that [barbecue] was first introduced into this country by the early settlers of Virginia” and the considered practice, “commonly looked upon as a pleasant invention of the Old Dominion.” Europeans and later Americans desperately tried to culturally remove themselves from the people whose cooking styles and methods they had adopted, going as far as to invent false origin stories to help bolster their arguments. The process of cultural appropriation seemed to come full circle in subsequent passages of Lanman’s work, as he concluded that a review of the practice of barbecuing “deserves more praise than censure, as we know of none which affords the stranger a better opportunity of studying the character of the yeomanry of the Southern States.”[4] Thus, over the course of a couple generations, barbecue went from being an exotic American Indian cooking practice indicative of the supposed barbarism of indigenous peoples, to a peculiar “Old Dominion” invention, one that positively affirmed the cultural identity of white Americans in the American South.

Such cultural appropriation in the era was predicated on the appealing nature of barbecues both as a savory meal and an effective means to build community and influence political culture and elections. Following the War of 1812, Democrats seized upon the practice of large-scale celebratory barbecues as a means to unite the people and sway elections. As Andrew Jackson’s biographer Robert Remini describes, “Nothing beats food and drink to capture the interest of the American electorate. Even when the Democrats lost elections they seemed to think a barbecue was in order.”[5] The irony of celebrating Andrew Jackson—an infamous opponent of American Indian peoples—with a culinary tradition originating from American Indian nations was seemingly lost on the populace.

Regardless of the origin of barbecuing and the motives of its participants, the practice had become fundamentally associated with specific components of white American society by the 1820s. Descriptions of barbecues were filled with hyperbolic statements and weighty prose that spoke to the supposed grandeur and beauty of American society highlighted in these communal feasts. In his journal, the famed American naturalist John James Audubon detailed a barbecue in Kentucky in such a manner. “As the youth of Kentucky lightly and gayly advanced towards to barbecue,” he wrote, “they resembled a procession of nymphs and disguised divinities. Fathers and mothers smiled upon them as they followed the brilliant cortége.” The barbecue in question was a celebration of Independence Day, and on this day, Audubon felt “Columbia’s sons and daughters seemed to have grown younger that morning.”[6]

Audubon’s description of the Kentucky Independence barbecue addressed a number of tropes that had come to define the positive qualities of American national character. The event was an egalitarian affair, full of great energy, optimism, and a sense of communal pride. “The whole neighborhood joined with one consent,” he described, “no personal invitation was required where everyone was welcomed by his neighbor, and from the governor to the guider of the plough all met with light hearts and merry faces.” That all members of society (from “the governor” to the “guider of the plough”) were gathered at the event was an important component of Audubon’s description of American social egalitarianism. Further, the need to define community through nationalism in his passages was uniquely required in the western states, as questions regarding the ability of the nation to remain unified as its boundaries expanded remained an ever-present concern of the era. Audubon addressed these concerns by describing these “bold, erect” Kentuckians as “proud of their Virginia descent,” and pleased to “make arrangements for celebrating the day of his country’s independence.”[7] Therefore, even out west, Americans remained united through their shared political and cultural heritage.

Audubon continued by describing the food at the event as varied and plentiful and detailed how each participant in the barbecue “had freely given his ox, his ham, his venison, his Turkeys [for the feast, as well as] melons of all sorts, peaches, plums, and pears [that] would have sufficed to stock a market. In a word, Kentucky, the land of abundance, had supplied a feast for her children.”[8]

As they ate their meals, the participants sang the praises of their founders, further connecting the convivial meal with the American nation. The speeches, according to Audubon, “served to remind every Kentuckian present of the glorious name, the patriotism, the courage, and the virtue of our immortal [George] Washington.” As was customary in many large feasts of the era, toasts were also made to similar American political figures and national sources of pride. “Many a national toast was offered and accepted,” Audubon wrote, “many speeches were delivered, and many essays in amicable reply.” As the event came to a close, Audubon reveled in the scene he had witnessed. The barbecue had such a profound effect on the author, he concluded his “spirit to be refreshed every Fourth of July by the recollection of that day’s merriment.”[9]

While colorful and poetic, Audubon’s description of a Fourth of July barbecue was far from unique. As early as 1803, the Hornet newspaper publicized a “Republican Barbecue” to be held outside of Woodsburgh, Maryland. “It would be unnecessary,” the paper argued, “to describe the satisfaction, peace, and friendly intercourse that subsisted at this numerous and respectable meeting.” The paper continued by describing the event as a meeting of a “Band of Brothers,” with members “old and young—rich and poor—a meeting of freemen,” further exemplifying the supposed egalitarianism of American society.[10] The event also included a toast to numerous patriotic people and ideas, including the president of the United States, the political concept of republicanism, and a toast against traitors such as Benedict Arnold and—not surprisingly for a Democratic-Republican event—John Adams.[11]

However, barbecues were not relegated only to the southern states. A Fourth of July barbecue was planned for Madison, Wisconsin, in 1843 and described by the local paper as “evidence of the taste, beauty, good cheer, and patriotic ardor” of the town.[12] After the usual set of toasts and patriotic songs, the paper proclaimed the attendees would “partake of the numerous excellent viands, rarities, and delicacies … prepared by the united liberality of the citizens of Madison.”[13] Although the festival occurred in one of the northernmost towns in the country, the Madison Fourth of July barbecue remained surprisingly similar in tone and procedure to its southern equivalents. The unifying nature of such celebrations was seemingly easy to replicate throughout the nation. Indeed, barbecues remained the quintessential method of celebration in the early Republic, fusing the burgeoning American national cuisine with the ideals of the developing American political and social culture.

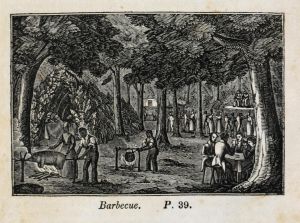

Regardless of the barbecue’s perceived inclusive nature, however, these celebrations of freedom through commensality remained stolen from the practices of an oppressed native population, and—equally disturbing—were often prepared in the southern states by the enslaved. For instance, in the engraving accompanying a description of Virginia barbecues, Samuel Goodrich’s travelogue alluded to the fact that black slaves lit the barbecue pits and cooked the meals for their white masters. In the visual, a black man and woman are seen turning a whole hog on a spit, while another young black man stirs a pot near the fire. White men dressed in formal attire relax under a tree and play cards, while a group of white women and children dance in the background. The master/servant relationship was in full effect in the visual, yet Goodrich did not mention this fact in his written account. In contrast, Audubon did mention black slaves in the description of the Kentucky barbecue he witnessed. In passing, Audubon wrote that “for a whole week or more many servants and some masters had been busily engaged in clearing an area [for the barbecue].”[14] But beyond this observation, Audubon never returned to discuss the further actions and impact that slaves had on the day’s festivities.

“Barbecue,” engraving, in Charles A. Goodrich, The Universal Traveller, Designed to Introduce Readers at Home to an Acquaintance with the Arts, Customs, and Manners, of the Principal Modern Nations on the Globe (Hartford, CT: Canfield & Robbins, 1836), 39.

Regardless of the lack of references in these accounts, it is clear that slaves held important roles and responsibilities in southern barbecues. On large plantations as well as in private homes, slaves often generally served in culinary roles as food cultivators and chefs, and it is logical to assume that they took their knowledge and practices in daily meal preparation and applied it to barbecue festivals. Louis Hughes, a former slave who recounted his enslavement in Virginia in his memoir Thirty Years a Slave, described in detail the intricate barbecue cooking practices of enslaved cooks:

The method of cooking the meat was to dig a trench in the ground about six feet long and eighteen inches deep. This trench was filled with wood and bark which was set on fire, and, when it was burned to a great bed of coals, the hog was split through the back bone, and laid on poles which had been placed across the trench. The sheep were treated in the same way, and both were turned from side to side as they cooked. During the process of roasting[,] the cooks basted the carcasses with a preparation furnished from the great house, consisting of butter, pepper, salt and vinegar, and this was continued until the meat was ready to serve.[15]

The barbecue style was indeed a complicated process, one that took many years to master and came with a generous amount of admiration within the slave community. Beyond the slave quarters, this cooking practice was also often well respected. Hughes described how it was common knowledge in the southern states that “slaves could barbecue meats best,” and consequently, “when the whites had barbecues, slaves always did the cooking.” Nevertheless, the power dynamics and social structure of slavery were certainly not forgotten during a barbecue, and even if there was a short moment of levity and celebration during the feast itself, it was merely, as Hughes wrote, only “a ray of sunlight in [our] darkened lives.”[16]

The juxtaposition of Independence Day celebrations prepared by enslaved peoples represented one of the starkest cultural contrasts inherent in food culture in the early American Republic. In most respects, the convivial nature of these and other public feasts was undercut by their ability to expose underlying injustices in American society. The inability to reconcile—and at times even to acknowledge—these issues in certain written descriptions spoke to the fundamental prejudice and inequality that pervaded American society. By the turn of the nineteenth century, Americans had shed their postcolonial identity in favor of a stronger national sense of self. But what Americans implemented nationally in its stead exposed inherent complications and contradictions in their society. In this new system, food and cuisine remained a symbolic representation of the American people, both for good or ill. And in Fourth of July barbecues of the era (culinary practices appropriated from oppressed native peoples and prepared by enslaved populations) the colorful nationalistic language and haughty calls for unity that accompanied the communal feasts and festivities often rang hollow for large swaths of the population.

[1] Charles A. Goodrich, The Universal Traveller, Designed to Introduce Readers at Home to an Acquaintance with the Arts, Customs, and Manners, of the Principal Modern Nations on the Globe (Hartford, CT: Canfield & Robbins, 1836), 39.

[2] For a detailed description and observations of early barbecuing in North America, see Andrew Warnes, Savage Barbecue: Race, Culture, and the Invention of America’s First Food (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008).

[3] In his work, Warnes details the complex history of the concept of barbecue—including its associations with Native Americans and savagery—and also describes the inability to easily ascertain the etymology of the word itself. Often the word is attributed to the Arawakan phrase barbacoa, meaning “a roasted animal.” But there is also a connection to the general concept of barbarism that European colonizers associated with native peoples. “Barbecue mythology arose,” Warnes writes, “neither from actual Arawakan life nor from any other indigenous culture, but from loaded and fraught colonial representations that sought to present those cultures as barbaric antithesis of European achievement.” Warnes, Savage Barbecue, xxii.

[4] Charles Lanman, Haw-Ho-Noo; or, Records of a Tourist (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Grambo, and Co., 1850), 94, 97.

[5] Robert Remini, Andrew Jackson: The Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981), 382–383.

[6] John James Audubon, “A Kentucky Barbecue,” in Audubon and His Journals, edited by Maria Audubon (London: John C. Nimmo Press, 1843), 487.

[7] Audubon, “A Kentucky Barbecue,” 488.

[8] Ibid., 487.

[9] Audubon, “A Kentucky Barbecue,” 488.

[10] “A Republican Barbecue,” The Hornet (Frederick, MD), October 25, 1803, 1.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Fourth of July,” The Wisconsin Democrat (Madison, WI), June 22, 1843, 2.

[13] “Fourth of July,” The Wisconsin Democrat, 2.

[14] Audubon, “A Kentucky Barbecue,” 487.

[15] Louis Hughes, Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom (Milwaukee, WI: South Side Printing Company, 1897), 49.

[16] Ibid., 50, 51.